Droppin’ Science in the Emerald Isle | The EQ Issue 5

In a recent article for the EQ Magazine Mikal Amin Lee recalls trip to Ireland with WBL where they participated the seventh annual Droppin’ Science Global hip-hop conference.

Be honest, when you read or hear the word “Ireland,” is hip-hop the first thing that comes to mind? I’d wager probably not. Yet if you have a chance to visit the “Emerald Isle” I think you’ll walk away with the knowledge that it is indeed there. This past spring, Words Beats & Life and I were invited to be a part of the seventh annual Droppin’ Science Global hip-hop conference. The conference is hosted and organized by the University of Cork in Cork, Ireland, in partnership with the European Hiphop Studies Network (EHHSN), a “group of artists, practitioners and researchers interested in sharing and expanding knowledge of hip hop culture.” The network publishes an academic peer-reviewed journal and is working on a 3D AI search engine in addition to the annual conference. All of the network’s endeavors are meant to fulfill their stated goals to:

“Cultivate a cipherial hip-hop ethos inside academia, such as respect, circulation and exchange of knowledge, and ‘each one teach one.’

“Validate the academic pursuit of hip-hop by transgressing the boundaries between the academy and the community

“Create a platform for networking and collaborations of different kinds, between European and non-European scholars and practitioners.”

The broad theme and focus for this year was to “bear witness to the strength of street knowledge.” The conference organizers stated that the event would, over the course of the weekend, “recognize hip hop as an organic intellectual arts practice and critically minded culture, building upon that foundation through workshops, conversations, performances, keynotes, scholarship, and fellowship.” But why Cork, Ireland? One reason is that one of the event’s organizers, J. Griffith Rollefson (a.k.a. “Professor Griff”), professor of music at the University of Cork, is based there. Different countries in Europe have hosted the conference since its inception, and this year it was Ireland’s turn. Cork is the “second city” in Ireland after Dublin. Relative to Dublin and other major cities across the world, Cork is quite small (a population of less than 250,000). However, it is known as a creative and cultural hub within Europe (it was named a European capital of culture in 2005). Cork in some ways is very much like a United States college town, with the University of Cork dominating the geography and a significant amount of activity within the city being influenced or springing from the university.

Walking through the city center and to the various campus buildings used for the conference, there is a beautiful mix of urban scenery and nature, with natural brooks and small forests dotted between residential houses and businesses. The feel of Cork is very much a working-class city, and its downtown gives off a strong punk vibe. You might think you stepped back in time to the ‘70s or ‘80s with the types of record stores, music shops and patrons I saw milling in the streets. The underpinning of style and edge I attributed in part to the typically liberal and multicultural environment that universities create through attracting students from wide-ranging places and backgrounds, and Cork is no different.

I spoke with Professor Griff and asked him why it was important to think about and honor the idea of “street knowledge”

“Since hip-hop has its own organic intellectual tradition rooted in other knowledges and traditional ways of being, we thought we’d use one of those ‘gems of knowledge’ — that classic track from Marley Marl and Craig G where they define Hip Hop beats and rhymes as forms of ‘droppin’ science.’ That is; it’s no mistake that for people who had been systematically denied access to education for centuries, valuable knowledge and codes would be inscribed into music, rhymes and dance moves. So we wanted to honor that tradition of science that’s not legible or valued in universities because of those histories of racism, sexism, classism and other forms of exclusion that universities really pioneered and perfected over centuries.

As we put it in the conference call: ‘For four days in May, we will dance about ideas, considering what it means to flip the script on the university knowledge trade and reimagine our relationship to science, Wissenschaft and all the narrow ‘ologies’ with which white Europeans claimed mastery over the world. For four days in May, we will build a ‘pluriversity’ ‘that is open to epistemic diversity’ and ‘not merely the extension throughout the world of a Eurocentric model presumed to be universal’ (Mbembe, 2015).

https://globalcipher.org/home/cfp-droppin-science-conference/

Because a lot of us are hip-hop kids who ended up doing their thing in university contexts — whether that’s in music, dance, linguistics, anthropology or whatever — we’ve all realized that Mbembe is right — that we can honor those knowledges AND do a sort of reparative justice work in universities to both value hip-hop’s way of knowing and remake the university into a truly pluralistic place not beholden to a singular and small-minded white colonial mode of knowledge production.”

Another conference organizer, the founder of the EHHSN, Dr. Sina Nitzsche, also weighed in on the importance of the conference and the network, expanding further on its purpose.

“The EHHSN is a research network which aspires to be community-oriented and community-driven. Its members consist of artists, scholars, educators and everybody in between. That is why the network has been connected with hip-hop culture since its beginnings.

Its meetings aim to bring together artists and non-artists from different disciplines, backgrounds and geographic locations to inspire exchange and collaboration. The inaugural meeting in Dortmund in 2018 aimed to connect artists, activists, educators and scholars to start a cross-disciplinary cooperation. The second meeting in Bristol in 2019 more forcefully asked about the role and meanings of elements in hip-hop culture and highlighted the desire for more equity with artist participation in academic spaces. Subsequent meetings in Rotterdam, Paris and Brno explored the role of practitioners in educational and cultural institutions. This year’s meeting in Cork succeeded in this important process by centering on artist contributions in keynotes, panel discussions, workshops, battles and ciphers.

Because of this, the network meetings have opened the previously rather exclusive academic spaces in Europe to not only include artists but to meaningfully engage with and honor their experiences. Members of the network see themselves as ‘facilitators,’ as American graffiti legend CARLOS MARE 139 was referred to at the 2015 Teach-In at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, which was organized by Words Beats & Life. To MARE 139, facilitators use their resources and networks to provide artists with opportunities to participate in institutionalized educational settings.

The idea of subverting and disrupting traditional norms and centers of power, while also reclaiming public and private (commercial) space, is at the very genesis of hip-hop’s formation. The idea of having a conference that centers organic intellectual production and research on a traditional and prestigious research university campus is a great example of what one of hip-hop’s ethos has always been about.”

Over the time we were present, I attended workshops run by professors, artists, activists and various hyphenates of those three! The subjects ranged from thinking about technology and what it means for hip-hop creative output to mental health and how hip-hop practice can help with trauma. The conference was designed to have a plenary of the participants at the start of each day, and each evening included a performance showcasing DJing and emceeing from local acts, attendees of the conference and some of the presenters (I got down in the rap cipher at one of the city’s more popular venues, “The Pav”). Words Beats & Life was invited to discuss our work creating the “Rap Laureate,” a yearly award that honors emcees whose contributions are significant to hip-hop culture and whose work inspires and educates young people from diverse backgrounds. Our talk and panel with me, co-author Dr. Jason Anthony Nichols and founder Mazi Mustafa as the moderator went into detail about our process of selection, why it’s important for the culture to recognize and honor its own impresarios and masters and why creating scholarship that is culturally relevant for the communities it wishes to engage is critical and important to the culture thriving. The discussion was robust, and what was of most interest to the audience was how we came to our two inaugural honorees, Lupe Fiasco and Black Thought. In particular, a large amount of time in the Q&A was engaging the audience in their selections for the next Laureate and also about how to further build out the process of selection.

This type of exchange, call-and response was a consistent component of every panel or workshop I attended. Unlike many conferences in which the lecturer presents their work and a polite inquiry ensues, almost every workshop I participated in was designed to encourage and engage dialogue, push-back, feedback and real-time problematizing of what was presented. Every presentation, panel and workshop truly was an active learning space and experience, not simply a place where the attendees were repositories for the presenter to pour knowledge into. Very much in the idea of hip-hop, “game recognize game,” and it wasn’t just presenters putting their attendees onto game — it very much was a cipher.

This type of exchange, call-and response was a consistent component of every panel or workshop I attended. Unlike many conferences in which the lecturer presents their work and a polite inquiry ensues, almost every workshop I participated in was designed to encourage and engage dialogue, push-back, feedback and real-time problematizing of what was presented. Every presentation, panel and workshop truly was an active learning space and experience, not simply a place where the attendees were repositories for the presenter to pour knowledge into. Very much in the idea of hip-hop, “game recognize game,” and it wasn’t just presenters putting their attendees onto game — it very much was a cipher.

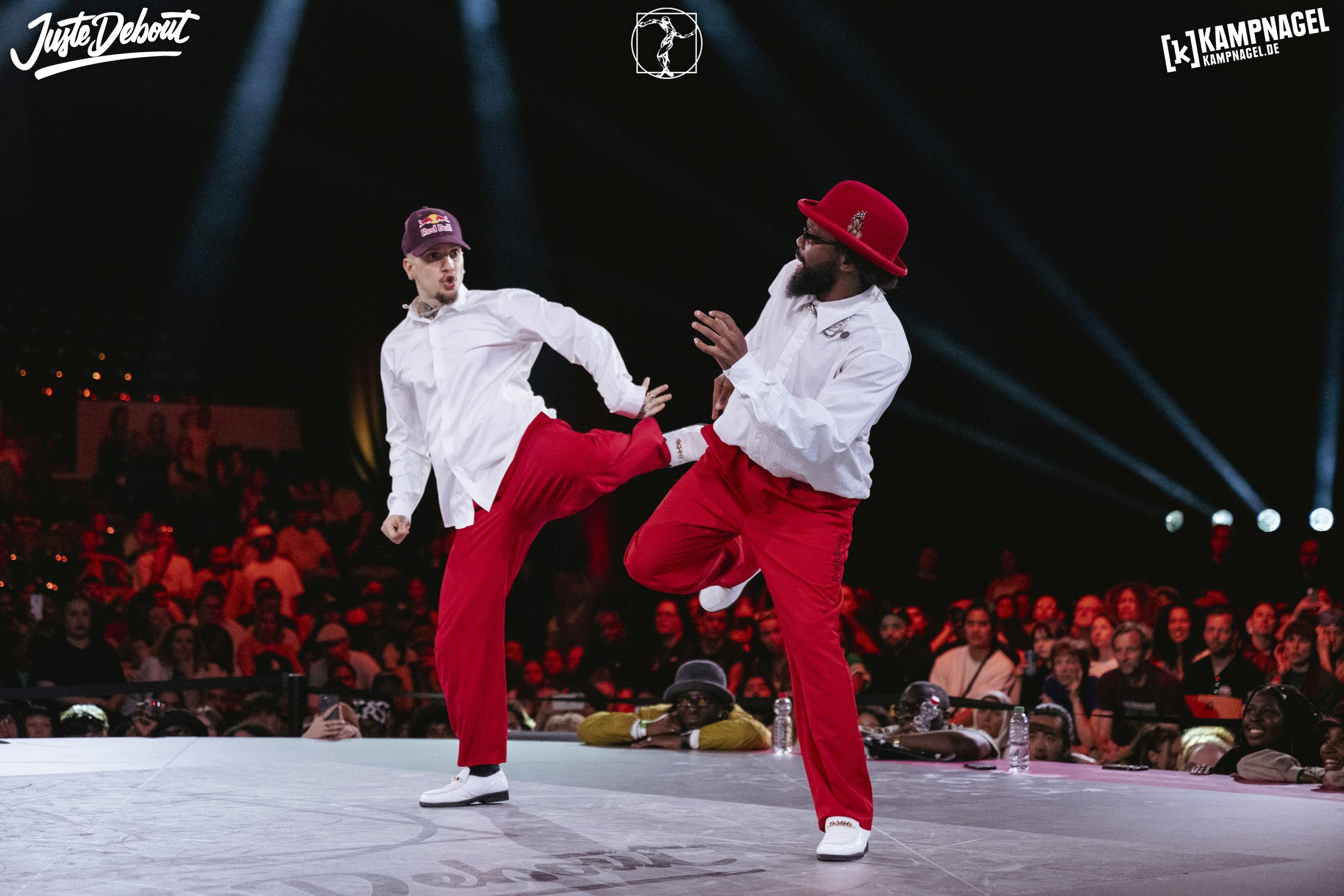

Two presentations really brought these ideas to mind, ‘I want a ceasefire / Fuck a response from Drake’: Spectacle and the War on Gaza presented by Adam Haupt and the breaking-in the Olympics panel with Jason Ng, Imani Johnson, Mary Fogarty, Frieda Frost and Tobi Omoteso. Adam’s session was actually a 20-minute choreopoem performance that incorporated video and visuals around the war. His scholarship embedded in the poem he recited with a cut-and-paste style collage of documentary and news footage and originally shot content. The idea was to present the friction and tensions of the war and the genocide in a way that demanded dialogue. It was beautiful, tense and powerful. Similarly, the panel discussing this year’s inclusion of breaking in the Olympics (more than two months before it would take place!) quickly turned into an open forum on its merits as well as its problems, which involved numerous voices in the audience, and not just the “experts” on the panel themselves. The dialogue and exchange were healthy, necessary and atypical of my experience at conferences, when many times the discussion is an echo chamber of sorts, whether out of politics, politeness or hegemony. “Droppin’ Science” in that way also was very much hip-op, be original, show and prove and keep it real.

With all of this going on, and as dope and as powerful as it was, the question still might be, Ireland and hip-op, is it really here? While Cork is a working-class city, it is still a city largely dominated by one of its biggest and most well-known universities. While there was engagement with the local community at the conference, and Cork is a city, the ideas of “street” or even “urban” don’t come to mind. Most importantly, Ireland is not a place that is predominately Black or Brown. Within that idea, Dr. Nitzsche talked about hip-hop culture at large within Europe:

“It is difficult to generalize ‘the [hip-hop] culture in Europe,’ as it is complex and multi-faceted depending on where you are. I think it is more appropriate to speak of ‘[hip–hop] cultures in Europe,’ which have shared and juxtaposed trajectories, [that] are both local and transnational and are overlapping and conflicting.

Over the past 10 years, there have been many important developments across Europe, such as the pandemic and its aftermath, climate change activism, digitization and new waves of global Black Lives Matter, feminist and queer movements in [their] localized versions. One of the major tendencies in my view is migration to predominantly Western European countries from diverse regions, such as Northern Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe, due to geopolitical conflicts and wars, the effects of climate change and the search for a better life elsewhere. In Germany, for instance, this has led to an increasingly multi-ethnic and multi-racial culture. In 2022, about 30% of the population had either a non-German passport or a history of migration in their families. This cultural development results in a reconsideration of what it means to be German.

Recent migration to Europe has also led to a backlash from (far) right-wing movements, anti-immigration parties, such as Rassemblement National in France, the Identitarian Movement in several countries or the Forum voor Democratie in the Netherlands. They hold on to traditional white-dominated notions of national identities. Violent riots that are currently taking place in several cities in the U.K. are also part of this far-right backlash against global migration.

Another important development happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 was streamed to literally every corner of the globe and of course, also in Europe. Some privileged groups of Europeans who have not really thought about structural racism in their lives have realized the dysfunctional effects of racism on people of color. This event resulted in protest movements across many European cities, such as London, Paris, Helsinki and Berlin. It also instigated a larger cultural reflection process on systemic police brutality, white privilege and social justice in dominant societies in Europe. Some cultural milieus are beginning to realize their colorblindness attitudes to race.”

Dr. Nitzsche outlined conditions that in part, can become a catalyst and an accelerant to create an artistic response, a cultural response. Hip-Hop is a culture founded by Black and Brown people as a response to a specific type of isolation, marginalization and erasure. However, as the culture has expanded, others who have experienced similar treatment have found hip-hop as a tool and a respite to be felt, seen, heard and respected.

Hip-hop culturally (not commercially) appeals also to people who may not be marginalized traditionally at all but still want to connect with themselves and their community at the root. This is something I felt in Cork. I asked Professor Griff, who, while an American, has lived and worked in Cork for years at the University. I wanted to hear from him, how hip-hop showed up in his city:

“The short answer is that, in Ireland, true hip-hop artists ‘dig where they stand.’ They find their authentic expression not by biting, but by doing their own thing — whether that’s by using Irish traditional music in their beats (like Scary Éire), rapping in Irish (like Kneecap) or focusing on Irish storytelling traditions and the famed ‘gift of gab’ (like my Ph.D. student, the MC 0phelia). My thinking about global hip-hop really evolved when I got to Cork and realized that MCs here look to their forebears — the epic bards of pre-colonial Ireland. Ireland is the only nation with a musical instrument as its national symbol — the harp. That’s the symbol because the ancient bards told their people’s history in rhyme. Who does that sound like? Y’all know the famed West African spike harp, the kora, right? And who do we associate with that instrument? The griots of West Africa — our most treasured hip-hop forebears. Well, this connection got me thinking that all peoples have those storyteller-poet-historians — we’ve just lost touch with them. Hip-hop has helped people around the world get back to that performed history. Not written history, but living breathing historians. That’s how hip-hop culture represents in Cork!”

So, Ireland and hip-hop may not be the first connection you make when thinking about the country, but it’s very much here, representing, thriving and, in Cork most certainly droppin’ science!